Christine Stampes erindringer om Thorvaldsen

Introduction

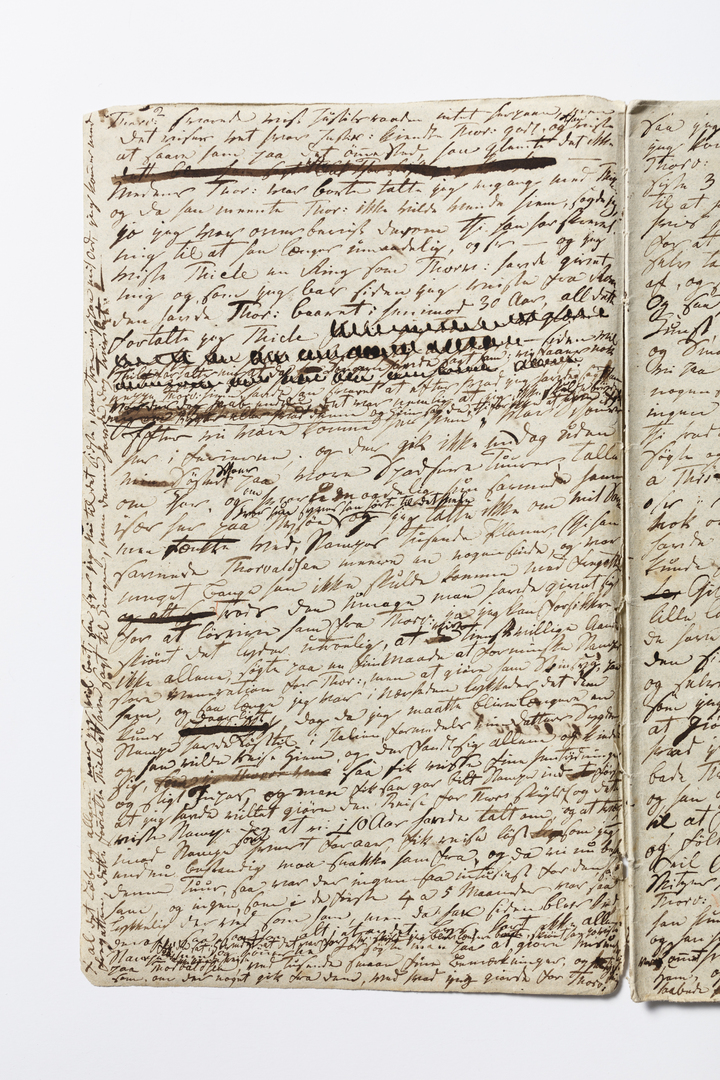

A page from Christine Stampe’s manuscript

A primary source

One of most important sources on Bertel Thorvaldsen’s later life and work is Baroness Christine Stampe’s (1797–1868) memoir of the sculptor, which was published in an edited version by Stampe’s granddaughter, Rigmor Stampe (1850–1923), in 1912.

Christine Stampe was Thorvaldsen’s closest friend after his return to Denmark in 1838. Among other roles, she acted as the sculptor’s ‘manager’, ‘image consultant’ and ‘career counsellor’, especially in connection with the establishment of Thorvaldsen’s Museum. For example, she helped him clear out – that is, burn – old papers, inappropriate drawings and other items to ensure that the remaining collection would appear presentable and fit for a museum. Her memoir was undoubtedly intended as a contribution to this effort to present the sculptor in an appropriate light.

Stampe wrote her memoir of Thorvaldsen in 1844–45 based on – now lost – journal notes with a view to publication as a book. She commissioned someone else – whose identity has remained unknown – to produce an edited version of the manuscript to be ready for publication, but the project came to nothing, because the edited text was simply too bland and dry. It was not until Rigmor Stampe revived the project by revisiting the original source, long after her paternal grandmother’s death, that the book was finally published, in 1912.

Background

Christine Stampe and her husband, Henrik Stampe, owned the barony Nysø near the town of Præstø in southern Zealand, where they lived with their children. Their home was a gathering place for prominent figures of the so-called Golden Age of Danish art and culture, including Thorvaldsen, who often stayed at Nysø after his return from Rome in September 1838 until his death in March 1844. The baroness and her husband opened their home to him, had a studio built for him in their garden, named ‘Vølund’s Workshop’, and also accompanied Thorvaldsen on his last journey to Rome in 1841–42. Christine Stampe in particular was a loyal companion to the sculptor during his final years. Her memoir of Thorvaldsen begins around the time of his return to Copenhagen and concludes around the time of his death.

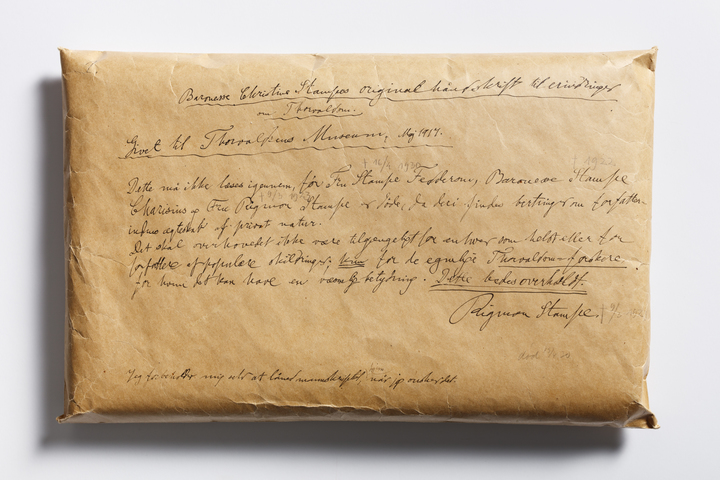

A manuscript with a proviso

In 1917, Rigmor Stampe donated both her grandmother’s original handwritten manuscript and her own edited version to Thorvaldsen’s Museum with the proviso that the original manuscript could only be read after her own death. The primary source is preserved under lock and key in the so-called Inspector’s Chest in a worn and faded envelope carrying Rigmor Stampe’s strict instruction:

Baronesse Christine Stampe’s original manuscript for her memoir on Thorvaldsen. Donated to Thorvaldsen’s Museum, May 1917.

This must not be read by anyone until Mrs Stampe Fedderow, Baroness Stampe Charisius and Mrs Rigmor Stampe are deceased, as it contains accounts of a private nature concerning the author’s marriage.

It shall not be made accessible to just anyone or to authors of popular expositions; only to actual Thorvaldsen scholars, to whom it may be of significance. Please abide by this restriction.

Rigmor Stampe

I reserve the right to borrow and take the manuscript home whenever I wish.

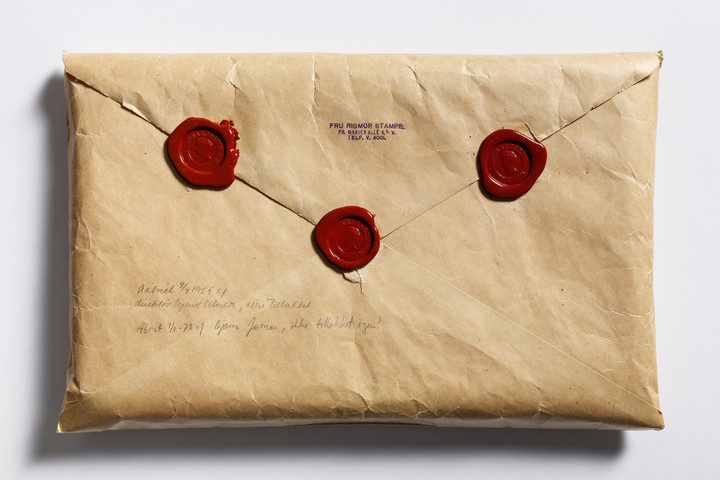

The back of the envelope is closed with three red wax seals.

On the back of the envelope, then museum curator Dyveke Helsted has written:

Opened on 4 April 1955 by Director Sigurd Schultz, resealed.

Eighteen years later, museum curator Bjarne Jørnæs inspected the content, noting – not without a touch of bone-dry archivist’s humour:

Opened on 9 August ’73 by Bjarne Jørnæs, not resealed!

The envelope contains 335 brittle pages with Christine Stampe’s memoir about Thorvaldsen written in pen and ink. The manuscript consists of six bundles, each held together with string, and a number of loose sheets.

The envelope is opened

Over the years, at Thorvaldsen’s Museum, Rigmor Stampe’s proviso naturally served to heighten curiosity about what stories from the original manuscript were omitted from the version that was printed and published in 1912. Since 2008, the museum’s archive has placed thousands of unpublished sources on Thorvaldsen’s life and work online at arkivet.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk. In light of this, Stampe’s memoir – as one of the most significant primary sources on Thorvaldsen’s later years – would make a peculiar omission if it were left out. Consequently, in 2017 – a hundred years after Rigmor Stampe’s donation to Thorvaldsen’s Museum – it was decided that the time was ripe for the unedited original manuscript to be released to the public. Viewed with the much greater distance to the events, it was found to be unproblematic – and important – to make the full memoir accessible to the general public, not least because the manuscript had been subject to proviso, censorship and editing. Ever since the work of Thorvaldsen’s first biographer, Just Mathias Thiele, Danish art history has gone to considerable lengths to sanitize the public image of the sculptor. One of the key purposes of the museum’s online archive, ever since it first went online in 2008, has been to peel off this reception history and seek out the original sources, whenever possible. From the outset, the work of the archive has been guided by the Renaissance humanists’ motto: Ad fontes! (Back to the sources!) – in part looking at the underlying basis of Thiele’s text. This ambition is the main reason to now unveil Stampe’s original, unedited Thorvaldsen portrait, which until 2017 was only accessible to a select few.

Grant from the New Carlsberg Foundation

In 2017, the Archive at Thorvaldsen’s Museum received a grant from the New Carlsberg Foundation to publish the original manuscript as part of Primary Sources in Danish Art History (PSiDAH). With this funding, the manuscript was photographed by Jakob Faurvig, transcribed by Birgit Christensen and published with annotations by Mads Aakjær Reinert and Ernst Jonas Bencard. The result can be accessed right here on the PSiDAH website and, in the latest updated version, in the online Archive of Thorvaldsen’s Museum.